This past May, I was invited to visit the University of Utah to give a couple of talks. One of them was for Erik Brunvand’s “Making Noise: Sound Art and Digital Media” course. It is a great class in which students from around the university gather to learn physical computing, basic electronics and a host of other things through the lens of music-making. I decided to use the opportunity to capture my thoughts on technology.

The title I gave to your professor for this talk was, “A Brief History of Technology.” 30 minutes isn’t enough time for a full history of technology obviously, but, it is enough time to think about what we mean when we talk about technology, and to consider the role it plays in creativity.

Like many things, there seems to be a period we’ll call BC (before computation) and AC, or after computation. Hopefully, this will help us get some perspective on a concept that captures our imaginations and frames the way we think about the technologies you all study and use in this class. Technology is really just a fancy word for tool. And tool is just a short word for artifacts we use to get things done. Rocks, when shaped in a certain way, become a technology for banging and cutting. People have been using this sort of high-tech gadget for a really long time. More advanced versions of this type of technology? Hammers. Ginsu Knives.

Then there is the ultimate in multi-purpose technologies, one that has drawn so much of human need and knowledge into a single, streamlined tool: the pocket knife. This path from stone to knife to pocket knife is the history of technological progression in a nutshell. We develop a need beyond human capabilities, and we find something that can help us achieve that need, and then we turn it into an over-featured salable good.

If you think about it, the computer, the thing that we nowadays assume we’re talking about if we talk about technology, is really just a fancy pocket knife for calculating and organizing. A sort of cutting edge abacus-card catalog combo with a built in file cabinet. We could already do most everything we do with computers before, albeit more slowly and less efficiently.

My point? That we should remember that computers are just another kind of tool. They aren’t anymore magical than being able to start a fire with two stones. This example also points to a really important consideration for technologies: they are part of processes we develop to achieve goals. Being able to start a fire by striking two rocks together to create a spark near an easily flammable material—that’s a process involving a couple of pieces of technology—the rocks—and some additional materials—a flammable material and some pieces of wood.

The history of technology has always been a coupling of tools, processes and needs. Tools are only useful if we have something we want to do with them. So those sharpened stones were good for cutting. And when combined with another stone and some flammable materials, to create fire for warmth, cooking and protection.

Tools aren’t always tangible objects we can touch. Sometimes, they are systems we create that provide conceptual structures for more easily thinking about and doing things. Human languages are an example of this. They are a conceptual framework for facilitating communication between people. Each language has its own vocabulary and organizing principles that allow us to understand one another. Language also fits the pattern of tool, process and use. Language allowed people to communicate with one another in order to plan, negotiate, share news, and so on.

I’d like to focus on the role of another ubiquitous yet intangible technology in our lives: math. Math is a technology we rely on so much we have ceased to recognize what it is: a set of structural tools for thinking about and making sense of the world. If we look at the history of subsistence-plus technologies, we see math use for all sorts of interesting purposes. I’m a game design and game scholar, so I can’t help but bring up an example from the history of games: the humble die. Best we can tell, dice are a 6,000 year old technology for probability that maps an array of numbers onto a cube.

In many cases, dice are functioning as a random number generator. They help us sort out how many spaces we’ll move around the board; they help people figure out if their elf or wizard were indeed killed by the dragon, or merely received a flesh wound. Beyond random number generation, there is another mathematic technology in play with dice: geometry. The basic forms of geometry are used to produce different kinds of random number generators by mapping arrays of different sizes onto different geometric shapes. This is some pretty complex technology, isn’t it? Three realms of math converge in these elegant tools we use to guide Uncle Moneybags around the Monopoly board.

One of the reasons I find dice so fascinating is they haven’t really changed much in 6,000 years. Yes, we use different materials, and we have much more elaborate methods for manufacturing them, but the basic technologies and uses haven’t changed substantially. This points to an interesting point in the recent history of technologies. We have grown to think that technology must always progress, that it gets better and more powerful with each passing day. No one can argue that computational devices aren’t way more efficient than duck-taping an abacus, a typewriter and file cabinet together, but they aren’t the replacement for everything that has come before them. There is a long history of technologies that are just as important, if for nothing other than one simple fact: computers exist because of typewriters, looms, abacuses, microfiche and all sorts of other tools.

One way to keep perspective on computers: they are really, really fancy calculators. The very name, computer, belies the mathematical underpinnings: a thing that computes or calculates. These devices are really just incredibly complicated abacuses that we’ve figured out how to push to do all sorts of useful and entertaining things. Like dice, computers are made of layers and layers of technologies: math, but also language, and electronics, itself built on another dose of math mixed with physics. And the material form of computers requires other forms of math plus chemistry, and so on. You get the point: computers are these super-complex tools we’ve built out of a bunch of other technologies.

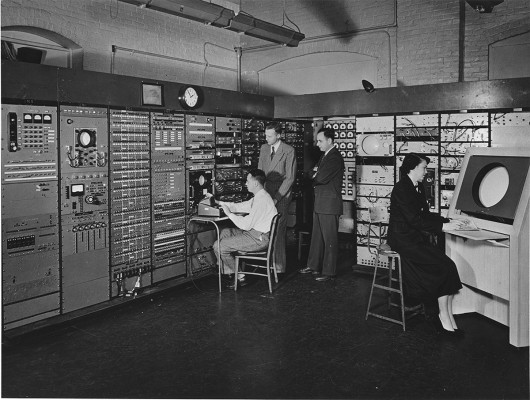

We think of computers today as these Swiss Army knives that let us accomplish a bewildering range of tasks, and that let us have all sorts of experiences. They weren’t always so multi-functional, though. Going back to their roots, computers were weaving machines, or math machines, but not much more. It wasn’t until people like Ada Lovelace, Alan Turing, Vannevar Bush, Grace Hopper and Douglas Engelbart got involved that we started thinking about them more broadly.

It was Ada Lovelace who first connected algorithms to computational machines. She was an English mathematician who studied and theorized around Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine. The Analytical Engine was a proposal for a general-purpose computer. Lovelace closely studied the plans, and theorized programs that could be run on the machine. She had a vision for how the computational device could, “… act upon upon other things besides number….”. Sadly, the Analytical Machine was never built, and so Ada’s theories were left untested.

It was Alan Turing who used mathematics to prove how computers could be useful for purposes beyond number-crunching. He is often referred to as the father of computer science, as he was able to reconsider the uses of these calculating tools for a broader set of uses, such as playing chess. One of the more important observations Turing had was that a computer could take on anything that could be expressed mathematically.

It was Grace Hopper who strove to make programming more accessible. She developed early compilers that allowed more people-friendly ways to program computers. Hopper believed it was important that programming languages be closer to English than cryptic strings of numbers and letters. She was also an advocate for moving from large centralized mainframes to networked computers, which further increased access for more people.

It was Vannevar Bush who imagined computers as a means of storing and accessing all of human knowledge. In the 1930s, Bush conceived of the Memex, a machine that used film to create an encyclopedia of books, documents and other printed materials that could be cross-referenced and organized to supplement the user’s memory. The Memex remained a concept only, though it influenced the eventual invention of the internet.

And finally, it was Douglas Engelbart who saw computers as an extension of the human mind. He was concerned with using computational tools to extend what people were capable of doing, or what Engelbart called “augmenting human intellect”. Engelbart knew that for these new tools to be truly useful, they needed to be more accessible. And so as part of a larger project to network locations, he and his team invented the mouse and the graphic user interface. With these tools, it was easier for people to make sense of and interact with computers.

The point with these five people is this: tools aren’t just there, they become. And the processes we create to help us use these tools are borne from our goals for what we’ll accomplish by using the tool. This happens through a confluence of desire, understanding and use. People desire to do things, and they turn to tools to help them act upon the desire. To know which tool to use requires an understanding of the available tools and how they can help fulfill that desire. And deep understanding most often comes from use of the tools. That’s a functional take on the history of technology. People have developed tools around certain uses, with processes emerging for how to use them to meet human needs. And often, we find new uses for these tools, which lead to new processes, and so on.

In this class, y’all are concerned with creative uses of technology, right? There’s a long history there, too. Pretty much as soon as culture emerged, people started making things. Some of them were useful, like farming equipment, while others were useful in what we’d call subsistence-plus ways. By that I mean uses that go beyond the basic needs of sustenance, shelter and protection.

We start finding ways to use our tools for things like play and entertainment and not just for utilitarian purposes like feed and cloth and shelter ourselves. This is where music, visual art, theater and so on come into play. Sometimes, we use the same tools for both utility and enrichment, sometimes there are separate sets of tools used.

We can look back in the history of art and see that it also a history of technology. Let’s look back at the example of dice, the first examples going back some 6,000 years. They were used for forecasting and other spiritual intentions, but they were also adopted for play and gambling.Fairly early, people saw the there was a use of a tool to create something else—play. It took someone understanding the basic use of a die—probability—and coming up with a subsistence-plus usage for it. We find flat, round dice-like objects connected to the ancient Egyptian game of Ur. And dice were used for gambling in ancient Roman times, and later, in stories recounted in the bible.

It’s worth pausing for a moment to think about how the general understanding of technologies informed their artistic applications. Let’s return to mathematics as a technology of knowledge production. During the late medieval period, math was considered a means of unlocking the secrets of God’s creation of the world. (“thou hast ordered all things in measure and number and weight.”) By being able to quantify the known world, it was thought that the secrets of God’s intentions might be better understood and appreciated. For the visual arts, this translated into an increased concern with the accurate representation of the visible world. This connection between mathematics and human interests fed into the arts, have a huge influence on what was created and how the art was created.

With this in mind, let’s look at painting in western Europe during the late Medieval period. The main subject matter was religious, typified by a work like this by Cimabue from the late 13th century. Though it isn’t easy for our contemporary eyes to discern, Cimabue wanted to create more realistic representations of the world. Part of the drive was to make the people and situations described in scriptures as tangible as possible.

Jumping ahead only a decade, we find Giotto, another Italian artist who is also pursuing a heightened sense of realism with his work. Giotto has taken the same tools and techniques used by Cimabue, and pushed them to new ends. He saw different potentials in combining the technologies of image-making—pigments, water, animal hair, and wooden sticks— and the systems of visual art—geometry, color, composition.

There is still a strong functional element to Giotto’s paintings—telling stories from the books of the bible—but there was a shift in the balance between purpose and style. These were all put to artistic ends that required a different kind of understanding of the potential of the various tools. With them, Giotto created what are in effect some of the finest graphic novels created on the walls of religious buildings in Italy.

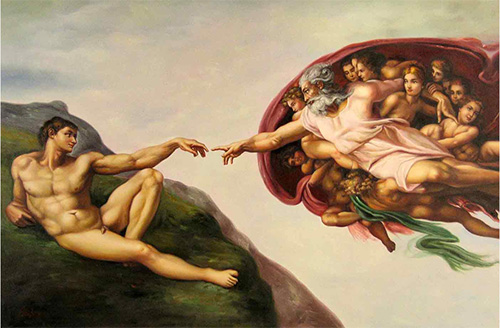

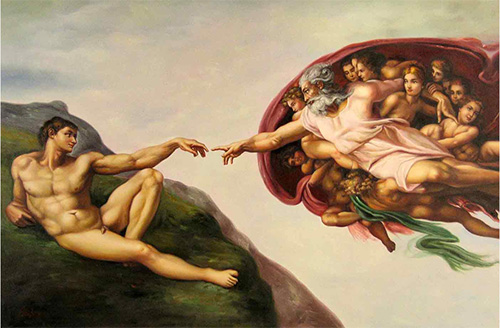

The trajectory of modern western visual art is informed by this conception of the world. Michelangelo is considered the pinnacle of the representation of the visible world. By the time we got to Michelangelo and the early 16th century, roughly two hundred years after Cimabue and Giotto, the mix of technologies of creation and knowledge-making were influenced not by just trying to understand nature of the world, but to better it. So instead of trying to faithfully represent the visible world, artists like Michelangelo tried to one-up nature. This is best noted in the ways he exaggerated the human form and the ways it moves.

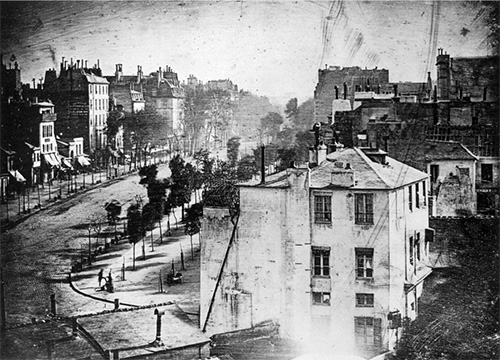

Jumping ahead 250 years, and we’re to the logical conclusion of representing the visible world: photography. The function of painting was suddenly questioned, as a new set of tools superseded the need for paintings—if all paintings were for was representing the world around us, why make them anymore? A 100 year period of angstful contemplation unfolded, resolving more or less with a urinal, and a Brillo box, among other things. Photography caused artists to question everything about painting: its tools, its processes and its purpose. This isn’t to say painting is no longer relevant, but that it went through a long period in which it was a set of technologies in search of a new purpose. Yet people continue to paint, and if you consider a broader range of subjects, paint with very similar goals—representing the visible world—with tools not so different than those Cimabue and Giotto used 700 years ago.

Let’s look at one more example of creative technologies: those of hip hop. The tools of hip hop have changed over the last 40 years, but they have also stayed the same: tools for cutting and mixing. Hip hop emerges from the NYC street party scene where DJs were developing ways to keep a party rolling without stops between songs. This may seem like an oversimplification, and it is, but the fact remains: hip hop music initially emerged as a means of keeping a party going.

The tools of the trade were two turntables, a mixer, a microphone and crates full of records. The DJs up in the Bronx figured out how to use two copies of the same record to create extended versions of a song, and to overlay pieces of two songs to create a new one, or simply to create a bridge from one song to the next. In the process, DJs discovered that their turntables weren’t just playback devices, they were instruments in their own right. They could be played to create new sounds out of the pre-recorded tracks.

These base technologies were supplemented with things like reel-to-reel tape machines to allow DJs to record mixes ahead of time so they wouldn’t have to always perform everything live. And there were digital tools like the drum machine and the sampler. Drum machines made it easier to replicate a great break, or create a new one. And samplers brought the storage and processing capabilities of computers to make it easier to build songs out of the pieces of other songs.

But at the end of the day, the point of all this music and its tools was keeping a party going. The tools of hip hop have changed over the last 40 years, but they have also stayed the same: tools for cutting and mixing. As this hip hop example points out, the history of creative technologies is often a history of exploration. By that I mean artists and designers are simultaneously pursuing creative goals and testing the potential the tools at their disposal to see what new expressive and experiential goals they discover.

In many ways, this class is not so different than what DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, African Bambara and Grand Wizzard Theodore were pursuing in the parks and clubs of the Bronx. In this class, you all are exploring the potential of your toolsets to create music. The differences lie in the contexts for sure, but also in the technologies you are using to create. Instead of mostly physical tools—turntables, mixers, and records—you are using the more language-based technologies of programming and music theory.

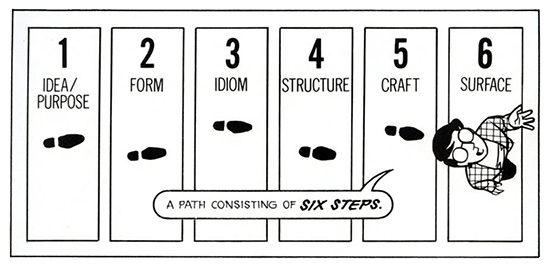

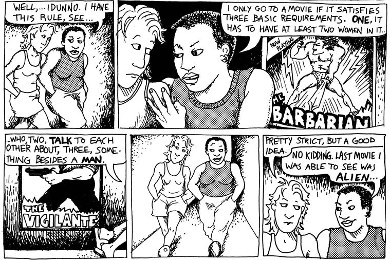

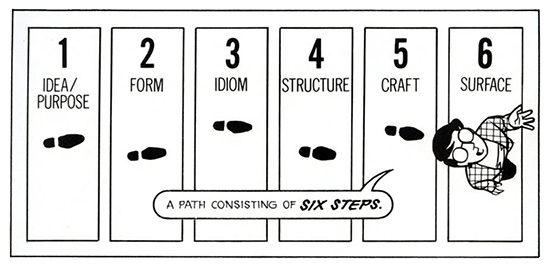

It’s hard, isn’t it? One of the best descriptions of the challenges of creativity I’ve ever found comes from Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. He describes a six-part journey from being a fan to becoming an artist. Though he doesn’t frame it this way, he is telling the story everyone goes through in mastering the technologies of their craft.

We begin with imitating the surface details of the given medium. We try copying the methods we know or imagine are used to create work in the medium. This is often about mastering the basic technologies of the medium—drawing with pen and ink, strumming a guitar, writing basic programs.

At some point, we get a handle on this, but we also begin to see there is much more than just knowing how to use the tools. There are all sorts of invisible technologies of knowledge we need to understand—color theory, geometry, musical scales, chords, and so on. These invisible technologies are the basic principles governing the medium.

Then we realize there is another level of craft—that of the medium, and the underlying language of the medium. In comics, that might be the frame, in music, time signatures, chorus-verse structures, and so on.

Once we understand that language, we find there are more nuanced idioms that allow more fine-grained communication through the medium. The conventions of genres, which applies to music and comics alike.

After all that, we’ve come to master four successive layers of technologies: the basic craft skills, the principles that guide those skills, the principles of a medium, the particular language within the medium. And at this point, we are kind of back where we started, but with a more confident set of skills for using a set of technologies that allow us to create in ways we otherwise could not. We still have those nagging questions, though. What do we have to say? What do we need to express? And why this set of technologies? How are they strengthening our abilities in ways others could not?

This journey to mastering a craft isn’t easy, as you all well know. Ira Glass, host of the radio program This American Life, has a great quote on this that I’ll end with:

“Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me. All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have. We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know its normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. And I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It’s gonna take awhile. It’s normal to take awhile. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”

The moral of this story? Though it probably seems like it, the technology isn’t the hard part. It is knowing what to do with the tools that is the real challenge.

The more we can focus on what we’re making, and why, the less mysterious technology becomes.