SUNBURN! and the giggles of death, in space

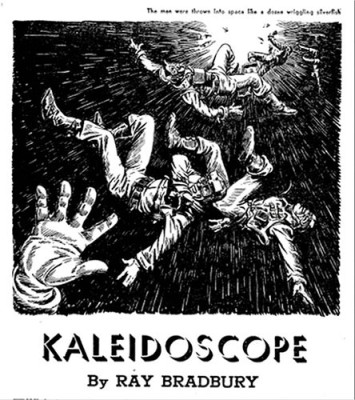

If we believe its developers, the game, SUNBURN! is an ode to the Ray Bradbury short story, “Kaleidoscope,” that first appeared in The Illustrated Man in 1951. Bradbury’s story opens in the moments just after a ship explodes in space, hurtling its passengers on divergent paths into the abyss. Everyone is left to contemplate their solitary death as they chat on their space radios, heading off to their deaths. They fight, lash out, weep, scream, reflect and generally contemplate their lives. Eventually, some of them come to reluctantly accept their fate.

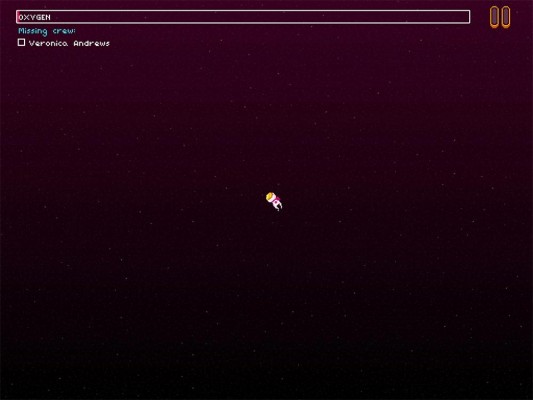

SUNBURN! takes this basic premise and twists it around a bit. Instead of everyone drifting off alone and bickering into their headsets, SUNBURN! asks you to kill off your crew in order to uphold the death pact you all made—no one dies alone!. All of this happens inside a physics-y puzzle game involving tiny little pixel characters lost in space.

As I thought about the game, I’ve tried to sort through why it resonates with me. I’m not always the biggest fan of SCI-FI, with all the space marines and BFGs and all, but there is something fascinating about the genre, particularly the mid-20th century era in which Bradbury wrote The Illustrated Man. Science fiction was pulp, a genre-bound pop form of mythological explorations of philosophical and political concerns—humanist thought wrapped up in gadgets and costumes. Science fiction was a place where things like the meaning of life and the solitary nature of death could be wrestled with. I saw glimmers of this in SUNBURN! before I learned of its connection to Bradbury’s story—life, death, community, meaning, honor, values, bonds.

SUNBURN! hits a nostalgia note for me, but not how you might think. I’m not a child of the NES or Gameboy or any part of the 8-bit and 16-bit eras, so it isn’t that. For me, SUNBURN! reminds me of Eugene Ionesco’s absurdist plays from the 1950s and 60s. Ionesco was a master at creating bittersweet humor from mundane situations turned in on themselves. Situations like a place where everyone turns into rhinoceros, or people have conversations about doorbells rung by no one, or rooms that inexplicably fill with furniture. Ionesco taught me that the commonplace, when reconsidered and put to work in unexpectedly absurd ways, proved to be an effective tool for thinking about the world around us.

SUNBURN! hits a similar note for me. The earnest, gleeful spin on tragedy and death tickles my absurdist funny bone. In the same way I love the absurdity of Ionesco’s The New Tenant and the way its characters matter-of-factly deal with a never-end stream of furniture over-filling their space. SUNBURN!’s captain and his crew likewise go about their business of carefully gathering together for one last leap into death. It is all at once sweet and stupid and cute and nihilistic.

One of the best ways to deal with unpleasant things, at least for me, is keeping occupied with simple tasks. Like washing dishes, or knitting or playing a game. And that is exactly what you get to do inside SUNBURN!—keep yourself busy with upholding important promises at the cusp of death. The game does this well I think. There are four basic gestures to the game—tapping to move your character, double-pressing to propel them, spreading to zoom in to see details, and pinching to zoom out to see more of the planetary system. I find myself getting quickly absorbed in these actions. I’m barely thinking about the fact I’m collecting my people to send us all to our deaths as quickly and efficiently as I can. We then all go into the sun, and the game gleefully celebrates that I’ve killed everyone, or kindly chides me for having left someone behind.

There’s a happiness in the apocalyptic vision of the game—in the cute graphics, the poppy color palette, the chirpy dialog. And a level of determination and stick-to-it-ness in the clever constraint-as-blood oath of “no one dies alone” at the core of the game. Everyone has an all for-one-one-for all attitude, even when left behind. And on the other side of death, after that act of abnegation driving the player character (which the other characters declaim, but don’t actively pursue, interestingly), the ghosts continue the peppy banter with comments about their afterlife.

In a lot of reviews, this has been pointed out as naughty or darkly humorous, and I can see why people think that, but I think that sells the game short. It is like stopping at the wackiness of people with rhino heads and not getting to the real substance Ionesco was working over, or only gawking at the explosion in Kaleidoscope and not really taking in what Bradbury has to say. My read of the completion of a level—good or bad—is an underlying belief in humanity, not a “dude, that’s fucked up” sort knee jerk you might see on MTV’s Ridiculousness or on a 4chan board.

There is darkness under the chippy veneer of SUNBURN!, if you want to find it. Within the game, something that always brings the direness of the pixel astronauts situation, and I suppose, of the fucked up world around us, are those moments when I lose my direction, or accidentally mis-aim and start drifting out into space. You quickly get out of sight of the planets, and are left drifting with a real sense of direction, nothing to anchor you or suggest which way to aim to insure contact with a planet. All that focus on the task at hand—joining up with your shipmates—disappears as you are out in the void, maybe tethered to a dog or cat, drifting off to nowhere.

This sort of moment makes me think of In the Dust of this Planet — the first book in Eugene Thacker’s philosophical horror trilogy. Thacker looks at black metal, horror movies and other genre fair in order to tackle the existential ideas we traditionally associate with philosophy. In the process, he looks at the vastness of the world that is just over there, just on the other side of our efforts to remain preoccupied. Indeed, something is always just around the bend to remind us of our insignificance.

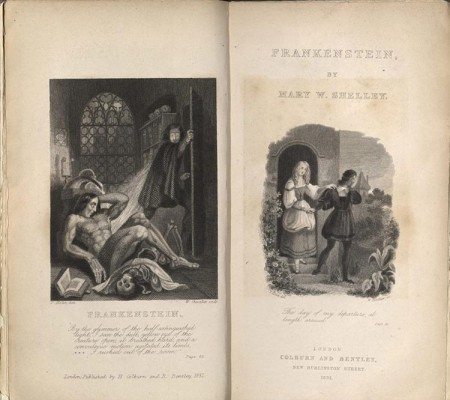

One of the things Thacker pursues in In the Dust of this Planet is a meditation on the limits of philosophy—it can only get so far on its own. Part of Thacker’s argument is that part of what the genre horror provides is a place we can explore things beyond the limits of philosophy. Take Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. It is a critique of enlightenment thinking, a meditation on the natural vs. the scientific, on the limits of human ability to create and control the world, of unintended consequences and so on. All told through a fable of an ambitious doctor and his monster in the scary woods. While Frankenstein isn’t necessarily in the required reading list of most philosophy programs, it is a great example of how genre can probe the human condition.

Though it never dawned on me back in high school and college, I now realize Ionesco was an existential fellow traveler of Bradbury and Shelley. Both were probing around the edges of humanity or the beginnings of late capitalism through their creations. But where Bradbury had rockets and control panels and robots and science, Ionesco had the mundane and the everyday. Shelley uses fantastically morbid monsters made of body parts to explore the limits of science, Ionesco uses people turning into rhinos to think about conformity and fascism and shifting moral foundations. So sometimes we can turn to Hegel, sometimes to Shelley, or, if you believe me, Secret Crush, to probe the human condition.

You could say, rightly, I’ve heaped a lot of high-falutin’ baggage on a simple physics puzzle game—and its true, I have. But the limits of what we as gamemakers think games can do is far more limited than what we usually give the medium credit for. If we look past mechanics and goals, and follow the trail of where games might lead a person to ponder—kind of like I’ve talked about here tonight—we can start seeing the real value of games. Yes, games are culture, but not just in the sense of creating or nestling into cultures. They are also Culture in the sense of an Ionesco play, or a Thacker book of critical philosophy, or, bringing us back down to earth, a Eugene Levy role in a Christopher Guest film.

We could look at Levy’s character Gerry Fleck as a down on-his-luck, two-left-feet goofus who triumphs in a Revenge of the Nerds sort of way, because that is certainly there. We can also see him as a sweet fable—everyone has a purpose that eventually reveals itself, bravery in the face of chaos, and so on—packaged in a work of mocumentary genre fare. That’s also there.

Inside of genre-bound works, we can have our fun and our smarts, all at once. That’s something that SUNBURN! reminds me of, and I appreciate that about the game. So thank you, Secret Crush.